View of the Frankfurt Kitchen, designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in 1926 and installed in over 10,000 housing units. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (January 23, 1897 – January 18, 2000) was the first female Austrian architect and an activist in the Nazi resistance movement.

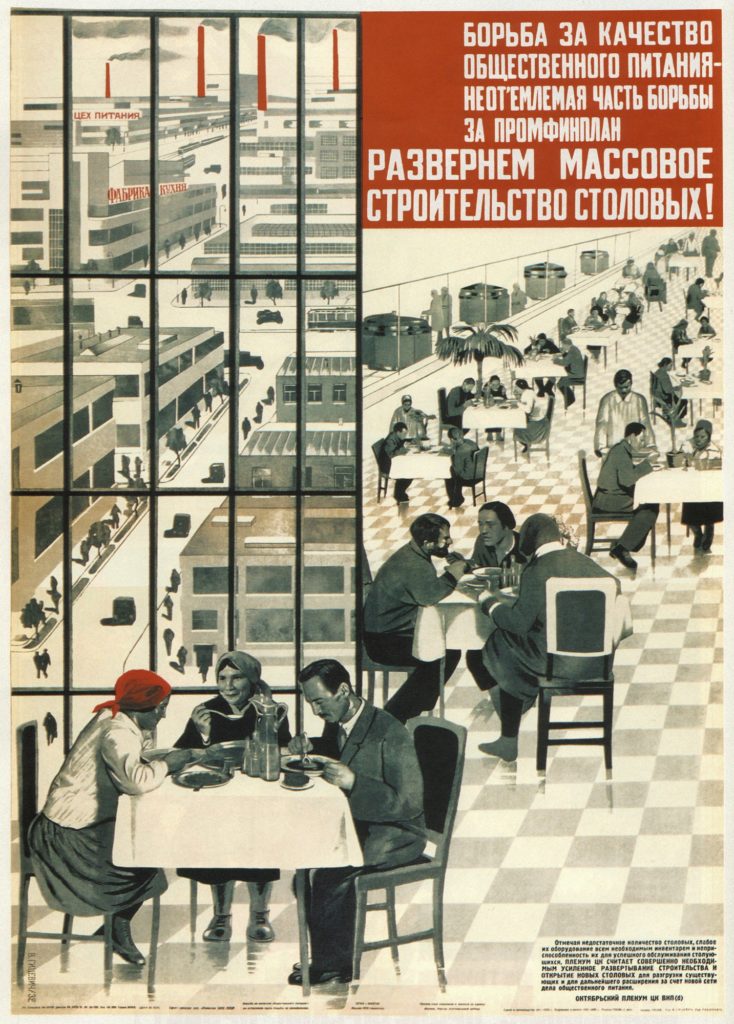

Sovremennaya Arkhitektura (Constructivist journal), 1931. The ‘social condenser’ is a key concept for the Russian Constructivist. In general, the term encouraged collective social consciousness and de-hierarchization of human interactions through the architectonic design of the public and private spaces.

Singapore’s Changai Airport food court, 2014.

January Suchodolski, “Battle at San Domingo” (1845). Depicting the struggle between Polish troops in French service and the Haitian rebels.

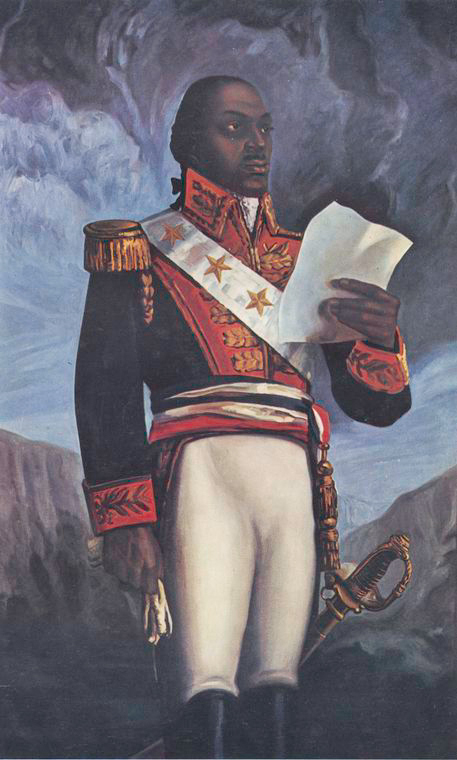

Général Toussaint Louverture” (1743-1803), artist unknown, found in 1957, collection The New York Public Library. Born in slavery, Toussaint Louverture bought his freedom in 1776, at age 33, and later became one of the leading figures in the revolution for the independence of Haiti (at the time, Saint-Domingue). As many historians agree, the character is difficult to grasp and has given rise to widely divergent interpretations. Some accounts portray him as an idealistic black-revolutionary emancipator and nationalist. Others, which stress the fact that Louverture himself owned slaves, portray him as a cynical political operator whose fundamental desire was his own benefit while being accepted into French society.

James Gillray, “Un petit souper à la Parisienne “(or “A family of sans-culottes refreshing, after the fatigues of the day”) (1792), Collection The British Museum, London. The cartoon is part of series that British caricaturist and printmaker James Gillray created in response to the reports published in the British press of the atrocities committed to what was later called the “September Massacres,” which included reports of cannibalism by some of the starving Parisians.

Theodor de Bry, Cannibal Feast (circa 1562), part of a series of engravings produced after the drawings John White, cartographer attached to several expeditions to the Americas.

Francisco de Goya, “Saturn Devouring His Son” (1820-1823). The work is one of the 14 Black Paintings that Goya painted directly onto the walls of his house sometime between 1819 and 1823. It was transferred to a canvas after Goya’s death and has since been held in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Saturn was the Roman name for the God of agriculture and the harvest, whom the Greeks called Kronos. He was the king of the lost Golden Age one hoped would return – the generous deity of abundance. But the Kronos cult also has another side, a dark prehistory: Kronos is the cruel father of the gods, who eats his own children.

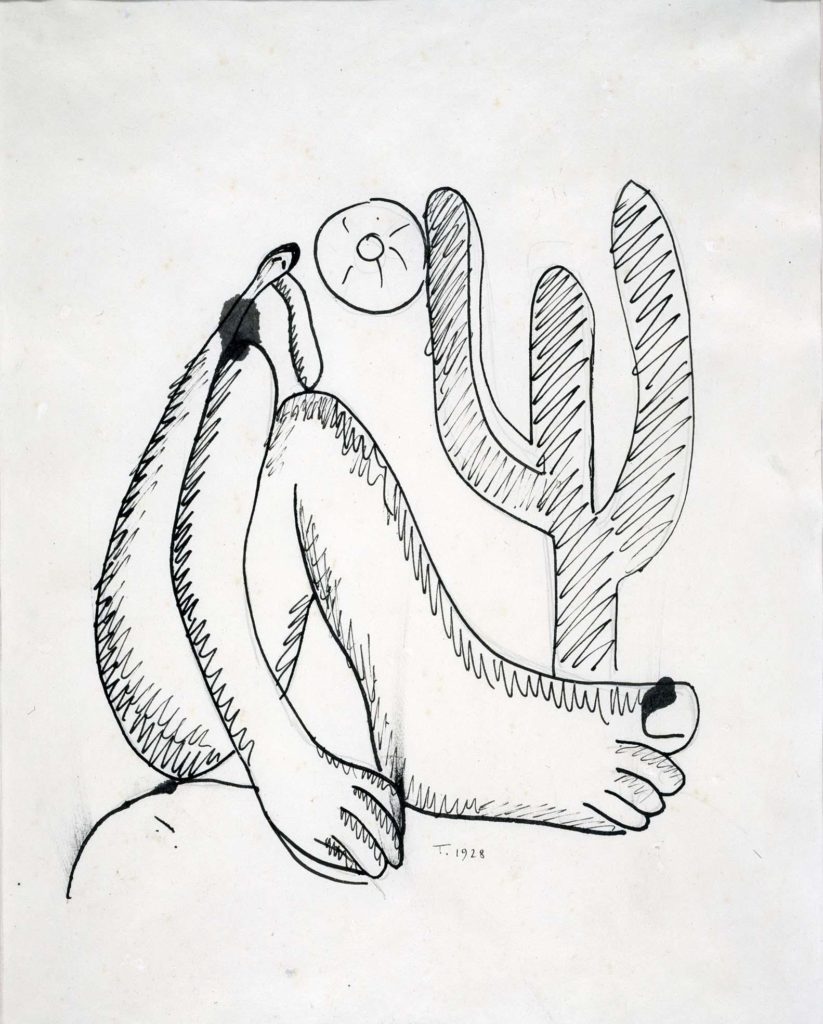

“Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporu VI” (1928). Ink and graphite on paper. Collection of the Reina Sofia museum, Madrid. Abaporu, which in tupi-guarani means “Man Who Eats Man”, was the first of Brazilian painter Tarsila do Amaral’s works to reclaim the concept of cannibalism or anthropophagy. The drawing was featured in the “Manifiesto Antropofágico” published in the “Revista de Antropofagia” in 1928 by Oswaldo de Andrade, poet, critic and husband of the artist, and which referred to the action of devouring foreign influences, carefully digesting them and then turning them into something new.

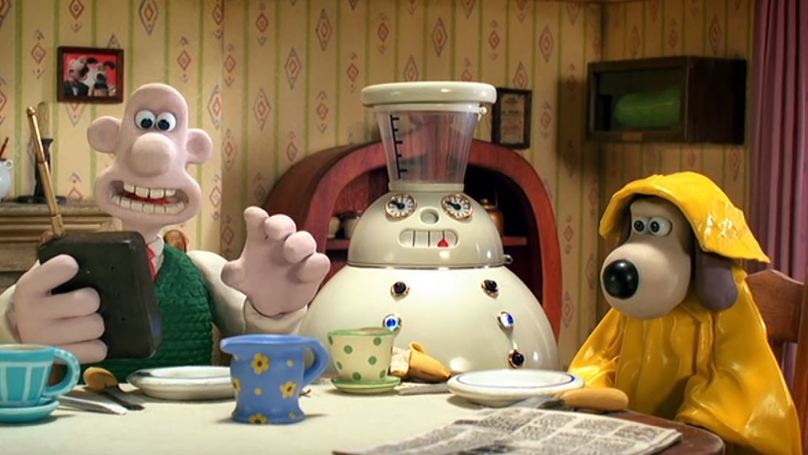

Wallace and Gromit, Cracking Contraptions: Autochef, stop-motion animation, 2002.

Links

-

A.

-

B.

-

C.

-

D.

-

E.

-

F.

-

G.

-

H.

-

I.

-

J.

-

K.

The following text also serves as a starting point of the eponymous festival, ‘A Matter of (In)digestions’, which is taking place in Amsterdam in May-June 2020.

(in)digestion as a trope for hyper-consumption:

the need to pause and the impossibility and unwillingness to do so.

In-di-ges-tion (n.), difficulty in digesting food,

accompanied by abdominalpain,

heartburn and belching.

Technical name: dyspepsia.

– Collins. English Dictionary.

A popular tradition warns against recounting dreams on an empty stomach.

In this state, though awake, one remains under the sway of the dream.

[…] He who shuns contact with the day, whether for fear of

his fellow menor for the sake of inward composure,

is unwilling to eat and disdains his breakfast.

– Walter Benjamin, “Breakfast Room,” in One-way street

I admonished them for this evil custom they touched

their lips and their bellies, perhaps to indicate

that the dead are also edible, or—but this explanation may be

far fetched—in order that I might come to understand

that everything we eat becomes, in the long run, human flesh.

– Jorge Luis Borges, Doctor Brodie’s Report

To sleep, to dream, to keep the dream in reach

To each a dream, don’t weep, don’t scream

Just keep it in, keep sleeping in

What am I gonna do to wake up?

– Kate Tempest, Europe is Lost. Let Them Eat Chaos

Historically, kitchens are places where major ideological, economic, and social transformations are experienced in the most intimate manner. In the nineteenth century, they became the focus of reformist attempts rooted in middle-class and racial assumptions about morality, science and technology. Kitchens were being transformed into a powerful ideological tool, sorting race and class, gender and power. In the following century, they evolved into a disputed terrain for modernist design. A case in point is the Frankfurt Kitchen[1], which was thought as an affordable design intended for social housing dwellings. Following an analysis of the processes and steps needed to produce a meal and organise the household, the design aimed at improving the domestic environment and therefore, women’s life. An unintended consequence of such an innovative approach, however, was the development of a bio-political device disciplining the body in an endless Taylorist dance[2].

The utopian vision of the kitchen as a collective space in which art and technology were combined with the promise of bringing about social change, drastically contrasts with the model of a modern kitchen. Turned into a pseudo-science-fiction machine equipped with refrigerators, freezers, electric ovens, microwaves, ice makers, toasters, mixers, centrifuges, decomposers, the latter becomes a symbol of social status— a token of the growing appetite for accumulation. In the age of the deregulated economies, kitchens metamorphosed into a new “all purpose office” that paradoxically recalls its pre-industrial function as a place where people would not solely cook, but perform their daily routines, conflating life, work and culture.

Experimental laboratories, gender prisons, architectural playgrounds and ideological battlefields, kitchens are at the heart of the contemporary homes. Paradoxically, these places of intimacy are currently being transformed into centers of speed in the hyper-connected world of the Internet of things. There, food production and supply lines are encoded in the houseware appliances designed to take autonomous decisions regarding offer[3], demand and taste: a novel iteration of “just-in-time manufacturing”[4].

The lack of a kitchen is a reality faced by millions of people worldwide. The migrant and the homeless, the war displaced and the inmate, the precarious worker, the soldier, the tourist and the patient are deprived of this space. They do not have the time or means to prepare their food. Their hunger needs to be satiated through a different strategy. During the Second World War, the highly rationalized and standardized industrial production line was adapted and used to feed armies competing for global superiority. As the fog of war lifted, this newly acquired knowledge about supply lines and mass-produced food was rapidly adopted by a fast expanding food industry, which relies on a complex network, encompassing agriculture, biotechnology, civil engineering, logistics, advertisement, and chain distribution. A tailored cooking style was born, propelled by a different kind of appetite which radically shifted the way food is perceived, thus consumed. A liaison between mass culture and mass-produced food, spiced by speed, colorful packaging and endless shopping lists.

And then, what does this craving imply? Eating and cooking go far beyond the act of ingesting nutrients for survival or preparing edibles for digestion. When we eat and cook we don’t only ingest and combine solids and liquids, but symbols, protocols, values, and literally centuries of history that come together in a single bite[5].

“A Matter of (In)digestions”

At the dock 3b in the back of the food court, a delivery from Hanover has arrived. Yellow and blue cardboard boxes containing a total of 30 kilograms of frozen Baby Lima Beans are unloaded from the truck. The farmer who grew the beans lives in the San Joaquin Valley, California. He paid 46 dollars in crop insurance for every square mile of land he farmed. Unaware of the traveling frozen beans that are now being carried next to her, she is sitting, wondering what to eat. In front of her, a conveyor belt is displaying items of all kinds. Golden, rounded madeleines; bowls of cold and creamy vichyssoise; chocolate bars; cups of hot tea; vegetarian rolls, slices of apple pies; a knife or two; bills and financial accounts; a compass; silver coins… On the television screen hanging in the corner of the ceiling, the weather forecast follows today’s news: tomorrow will replace today. Around her, flashy neon ads promote Vietnamese sandwiches, half-price Spanish chorizo, fruit sorbets, and low-cost flights. In the distance, the brouhaha of the cash registers and customers’ hurried steps overlaps with the sound of the television. Overwhelmed and hungry, she has to make up her mind—people are waiting to fill her tiny spot. She grabs a ball of fish and rice and guzzles it. She cannot believe it: the ball tastes insanely sweet, as if she had swallowed a loose lump of white pure sugar. It is an unsavory taste—uncanny. As the sweet chunk melts in her mouth, an image shimmers in her mind: Toussaint Louverture, a former slave and key leader of the Haitian Revolution, is standing in a salon, holding a text in his left hand and a pair of white gloves in his right hand. He wears a blue and red uniform coat and a sash decorated with stars. Around him, the walls are covered with images of animals and plants, maps and photographs from every corner of the world. In the center of the room, surrounded by an elegant company, small figurines made of sugar or rice are displayed on a large banquet table. They seem so real: she sees what they see and sometimes hear what they hear. The company seems particularly intrigued by the silent battle enacted by the figurines, and now surrounds the table, under the dazed eyes of the general who seems a bit confused and looks at her with a baffled gaze. His sugar troops will not resist the growing appetite of the guests, and with them will disappear his dreams of emancipation, wealth and power. On the eastern front, says one of the guests, sugar is scarce and the revolution repressed. Food is distributed using coupons. In the streets, the lines of waiting do not cease lengthening. In the room, the atmosphere becomes more and more thicker. A sudden metallic sound rumbles behind the wall, breaking the silence: it is a handcart. The frozen beans have reached their final destination. The delivery man presses the doorbell button, the alarm clock starts ringing: she opens her eyes, the rays of the morning sun bathe the room in a golden light. She thinks for a moment of the memories still fresh in her mind and wonders. She takes a shower, skips breakfast, and leaves the house.

In dreams, repressed desires and anguish become more acute, which can, at times, cause feelings of confusion, discomfort, or euphoria–and even provoke a sudden awakening. Nothing beats a morning breakfast: with every bite, darkness recedes. We leave the dream world, which fades into thinning memories. In a fragment entitled “Breakfast Room”, German literary critic Walter Benjamin suggests two possibilities in which awakening is not followed by breakfast, but rather continues throughout the morning: On the one hand, the energy of the dream is unleashed and can be channeled into truthful activity and artistic ventures; on the other, the dreamer endures the day like a sleepwalker–clouded in a grey dreamscape, the dreamer does not wake up and is therefore unable to take into account the concealed memories of his or her dreams. For Benjamin, the grey dream of modernity required shattering, the dreamer had to be awakened in order to untether the real potentialities of desire – if not of the dream itself. To decipher dreams on an empty stomach is to risk being unable to distinguish hallucination and daydream from vigil and presence, phantasmagoria from authentic desires. The act of ingesting or consuming paradoxically becomes an act of cleansing that facilitates awakening. While, for Benjamin, the greyness of modernity was to be redeemed through ingestion; for Brazilian poet, Oswald de Andrade (a leading figure of the modernist anthropophagy movement), the only way to confront modernity was to devour it. Within the contemporary context of cultural consumption and appropriation, anthropophagy–or cannibalism–becomes an ambivalent term that disrupts established imaginaries and identities. It is a malleable signifier that asks to be used and consumed, devoured and digested[6].

When apprehended together, both acts—to put an end to the nocturnal fasting and to stir up a devouring appetite as an act of cultural emancipation—become the twin sides of a flipping coin in the air. Both imply consumption and enzymatic assimilation, and both might cause indigestion: a dyspepsia that can result in hallucination. As the two-sided coin spins in the air, it blurs day and night, past and present, places and events. A delirium shading light into the materials and substances, protocols and symbols that we consume, and which indeed come together in a single bite.

By now, she has arrived at her workplace—a restaurant located in an airport at the periphery of the city. She is early and the kitchen is still deserted. She pours herself a coffee, which she stirs with distraction. She always adds a lump of sugar in her coffee, and this morning, it tastes different. Reminiscences of last night deeds take shape on the edge of her consciousness to then fade away, muted by the hasty sounds of wheeled suitcases. A new day has just begun. At the counter right next to the cashier sits yesterday’s newspaper, but there is no time to read. The frying machine needs to be warmed up and the break-fast items have to be put on display for the first customers who soon will arrive.

Notes

1. The Frankfurt Kitchen was designed by Viennese architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in 1926, for a housing project directed by chief city architect Ernst May. It was based on contemporary theories about efficiency, hygiene, and workflow, which from the factory were then applied to the domestic environment.

2. Horace B. Drury, Scientific Management: A History and Criticism (New York: Columbia University, 1915)

3. How is the Internet of Things (IoT) Transforming the Family Kitchen? On curiosity, use a search engine and look for this keywords.

4. Just-in-time manufacturing also is known as just-in-time-production or Toyotism was a logistical method aimed at optimizing supply lines. It was first implemented in Japan during the 1960s and was then widely used by diverse industries worldwide.

5. In his 1971 essay, ‘Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption’, French semiotician Roland Barthes argues that food is not only for eating anymore but has become “a system of communication, a body of images, a protocol of usages, situations, and behavior.”

6. We would like to note that we are referring in this text to the term antropophagia being aware of some of the historical biases and shortcomings in Andrade’s manifesto, as well as in subsequent readings or interpretations. In our view, the antropophago–the cannibal–is a powerful metaphor in discussions about ‘coloniality’, which nonetheless exceeds itself, becoming a traveling trope that points at uncharted contemporary territories. For a thorough analysis of the Anthropofagia movement, see the essay by professor Carlos A. Jáuregui, ‘Anthropophagy’, See also his book, Canibalia. Canibalismo, Calibanismo, Antropofagia Cultural y Consumo en América Latina (Madrid: Iberoamericana, 2008).